The developers of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine have previously undisclosed ties to the re-named British Eugenics Society as well as other Eugenics-linked institutions like the Wellcome Trust.

by Jeremy Loffredo and by Whitney Webb December 26, 2020

On April 30, AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford announced a “landmark agreement” for the development of a COVID-19 vaccine. The agreement involves AstraZeneca overseeing aspects of the development as well as manufacturing and distribution while the Oxford side, via the Jenner Institute and Oxford Vaccine Group, researched and developed the vaccine. Less than a month after this agreement was reached, the Oxford-AstraZeneca partnership was awarded a contract from the US government as part of Operation Warp Speed, the public-private COVID-19 vaccination effort dominated by the US military and US intelligence.

Though the partnership was announced in April, Oxford’s Jenner Institute had already begun developing the COVID-19 vaccine months before, in mid-January. According to a recent BBC report, it was in January that the Jenner Institute first became aware of how serious the pandemic would soon become, when Andrew Pollard, who works for the Jenner Institute and heads the Oxford Vaccine Group, “shared a taxi with a modeler who worked for the UK’s Scientific Advisory Group for Emergencies.” During the taxi ride, “the scientist told him data suggested there was going to be a pandemic not unlike the 1918 flu.” Because of this sole encounter, we are told, the Jenner Institute began to pour millions into the early development of a vaccine for COVID-19, well before the scope of the crisis was clear.

For much of 2020, the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine was treated as an early frontrunner, though its lead would later be marred by scandals related to its clinical trials, including the death of participants, sudden trial pauses, the use of a problematic “placebo” with its own host of side effects, and the “unintentional” misdosing of some participants that skewed its self-reported efficacy rate.

The significant issues that emerged during trials have provoked little concern from the vaccine’s two lead developers, despite critical attention from even mainstream media directed at its complications. The lead developer of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, Adrian Hill, told NBC on December 9 that the experimental vaccine should be approved and distributed to the public before the conclusion of the safety trials, saying “to wait for the end of the trial would be the middle of next year. That’s too late, this vaccine is effective, available at large scale and easily deployed.”

Sarah Gilbert, the other lead researcher on the vaccine, seemed to believe that premature safety approval was likely, telling the BBC on December 13 that the chances of rolling out the vaccine by the end of the year are “pretty high.” Now, the UK is expected to approve the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine shortly after Christmas, with India also set to approve the vaccine next week.

While the controversies surrounding the vaccine’s trials did ultimately undermine its previous frontrunner status, the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine remains heavily promoted as the vaccine of choice for the developing world, as it is cheaper and has much less complicated storage requirements than its main competitors, Pfizer and Moderna.

Earlier this month, Richard Horton, editor in chief of the Lancet medical journal, told CNBC that “the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine is the vaccine right now that is going to be able to immunize the planet more effectively, more rapidly than any other vaccine we have,” in large part because it is a “vaccine that can get to lower-middle-income countries.” CNBC also quoted Andrew Baum, global head of health care for Citi Group, as saying that the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine “is really the only vaccine that is going to suppress or even eradicate SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, in the many millions of individuals in the developing world.”

In addition to longstanding claims that the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine will be the vaccine of choice for the developing world, this vaccine candidate has also been treated by several outlets in the mainstream, and even independent media, as “good for people, bad for profits” due to the partnership’s “explicit intention of supplying [the vaccine] around the world on a not-for-profit basis, meaning that the poorest nations on the planet will not have to worry about being shut out of a cure due to lack of funds.”

However, investigation into the vaccine’s developers and the realities of their “no-profit pledge” reveals a very different story than that which has been spun for most of the year by corporate press releases, experts, and academics tied to the vaccine and the mainstream press.

For instance, mainstream media has had little, if anything, to say about the role of the vaccine developers’ private company—Vaccitech—in the Oxford-AstraZeneca partnership, a company whose main investors include former top Deutsche Bank executives, Silicon Valley behemoth Google, and the UK government. All of them stand to profit from the vaccine alongside the vaccine’s two developers, Adrian Hill and Sarah Gilbert, who retain an estimated 10 percent stake in the company. Another overlooked point is the plan to dramatically alter the current sales model for the vaccine following the initial wave of its administration, which would see profits soar, especially if the now-obvious push to make COVID-19 vaccination an annual affair for the foreseeable future is made reality.

Arguably most troubling of all is the direct link of the vaccine’s lead developers to the Wellcome Trust and, in the case of Adrian Hill, the Galton Institute, two groups with longstanding ties to the UK eugenics movement. The latter organization, named for the “father of eugenics” Francis Galton, is the renamed UK Eugenics Society, a group notorious for over a century for its promotion of racist pseudoscience and efforts to “improve racial stock” by reducing the population of those deemed inferior.

The ties of Adrian Hill to the Galton Institute should raise obvious concerns given the push to make the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine he developed with Gilbert the vaccine of choice for the developing world, particularly countries in Latin America, South and Southeast Asia, and Africa, the very areas where the Galton Institute’s past members have called for reducing population growth.

In the final installment of this series on Operation Warp Speed, the US government’s vaccination effort and race, the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine’s ties to eugenics-linked institutions, the secretive role of Vaccitech, and the myth of the vaccine’s sale being “nonprofit” and altruistically motivated are explored in detail.

GlaxoSmithKline and the Jenner Institute

The Edward Jenner Institute for Vaccine Research was initially established in 1995 in Compton in Berkshire as a public-private partnership between the UK government, via the Medical Research Council and the Department of Health, and the pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline. Following a “review by the [institute’s] sponsors,” it was relaunched in 2005 in Oxford under the leadership of Adrian Hill, who—prior to that appointment—held a senior position at the Wellcome Trust’s Centre for Human Genetics. Hill, the lead developer of the Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine, still leads a research group at Wellcome aimed at “understand[ing] the genetic basis of susceptibility to different infectious diseases, especially. . . severe respiratory infections,” which conducts most of its studies in Africa. The UK’s Medical Research Council has also become a collaborator with the Wellcome Trust, specifically on vaccine-related initiatives. The Wellcome Trust, discussed at greater length later in this article, was originally created with funding from Henry Wellcome, who founded the company that later became GlaxoSmithKline.

Hill’s partner at the Jenner Institute and the other co-developer of the Oxford COVID-19 vaccine is Sarah Gilbert. Gilbert also hails from the Wellcome Trust, where she was a “program director,” and is a student of Hill’s. Together, Gilbert and Hill have worked to position the institute to be the center of all future vaccination efforts undertaken in response to global pandemics.

The Jenner Institute’s relocation to Oxford was largely facilitated by the Medical Research Council, which donated £1.25 million between 2005 and 2006, after the decision was made to replace the institute’s original sponsors (GlaxoSmithKline, the Medical Research Council, the Department of Health) with the University of Oxford and the Institute for Animal Health, now called the Pirbright Institute. The involvement of Pirbright meant that the relaunched Jenner Institute became unique in developing vaccines for both humans and livestock.

The relaunched Jenner Institute has come to dominate publicly funded vaccine development in the UK as well as the testing of vaccines produced by the world’s largest pharmaceutical companies via clinical trials and has overseen prominent safety trials for vaccines of high media interest in recent years. Some of the Jenner Institute–conducted trials later draw controversy, such as those using South African infants in 2009 in which seven infants died.

An investigation conducted by the British Medical Journal found that the Hill-led Jenner Institute had, in the South African instance, knowingly misled parents about the negative results of and questionable methods used in animal studies as well the vaccine being known to be ineffective. The vaccine in question, an experimental tuberculosis vaccine developed jointly by Emergent Biosolutions and the Jenner Institute, was scrapped after the controversial study in infants confirmed what was already known, that the vaccine was ineffective. The trial, largely funded by Oxford and the Wellcome Trust, was subsequently praised as “historic” by the BBC. Hill, at the time the study was conducted, had a personal financial stake in the vaccine.

Similar instances of dodgy practices in efficacy trials and the effects of increased dosages have led vaccine experts to criticize the COVID-19 vaccine developed by Hill and Gilbert. Hill and Gilbert hold a considerable financial stake in the Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine. While the vaccine reportedly has an efficacy of over 90 percent, those figures—often cited in mainstream reports—are self-reported by the vaccine’s developers and manufacturers (i.e., the Oxford team and AstraZeneca), which is significant given that Hill and other Jenner Institute scientists have previously been caught manipulating trial results to benefit a vaccine product in which they were personally invested.

The prominence of the Jenner Institute in vaccine development and testing has largely come through Hill’s additional leadership role at the UK’s Vaccines Network, which chooses what vaccines to develop, how to develop them, and which firms should receive “targeted investments” from the UK government. The Vaccines Network also plays a key role in identifying “what vaccine technologies could play an important role in future outbreaks.” Two of the main backers of the UK’s Vaccines Network are the Wellcome Trust and GlaxoSmithKline.

Unsurprisingly, the Vaccines Network has steered many millions of pounds toward the Hill-run Jenner Institute, with completed projects including a “plug and display” virus-like particle platform for rapid-response vaccination. Also funded by the Vaccines Network were the Jenner Institute’s initial studies of novel chimpanzee adenovirus vaccines for coronavirus (in this case, MERS), the same viral vector used for the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine. In addition to the Vaccines Network, the Jenner Institute also coordinates the efforts of the EU’s Vaccines Network equivalent, MultiMalVax.

The Jenner Institute also has a close relationship with GlaxoSmithKline and the Italian biotech Okairos, which was acquired by GlaxoSmithKline in 2014. Soon after it was acquired, Okairos, and its new owner GlaxoSmithKline, became key players in the 2014 experimental Ebola vaccine push, an effort that mirrors the current COVID-19 vaccine development rush in many key ways. The rushed safety trials for that vaccine were overseen by Adrian Hill and the Jenner Institute and funded by the UK government and the Wellcome Trust. GlaxoSmithKline and Okairos are the only firms represented on the Jenner Institute’s Scientific Advisory Board.

The Jenner Institute along with GlaxoSmithKline-Okairos and a small French biotech called Imaxio have been developing an experimental malaria vaccine since 2015, with human trials of that vaccine announced on December 12, 2020. Those trials will be conducted on 4,800 children in Africa over the course of 2021, in many of the same countries where Hill’s research group at the Wellcome Center for Human Genetics has been studying genetic susceptibility to several diseases. “A lot more people will die in Africa this year from malaria than will die from Covid,” Hill recently said in regard to the soon-to-begin trials.

Currently, the Jenner Institute is funded by the Jenner Vaccine Foundation, but the foundation’s documents note on several occasions a considerable influx of money from Wellcome Trust Strategic Awards. A “special review panel” from the Wellcome Trust actually lobbied the Jenner Institute to apply for further “strategic core funding” from the trust after visiting the institute and appraising its work. The Jenner Institute frames its funding from Wellcome as the key guidance behind its development decisions, which are made “based on the successful model of Wellcome Trust Strategic Award support.”

The Jenner Institute’s foundation, however, is not the only source of income for its lead researchers. Hill and Gilbert have been working to commercialize many of the institute’s vaccines through their own private company, Vaccitech. Though media reports often describe the vaccine as being a joint effort between AstraZeneca and the University of Oxford, Vaccitech is a key stakeholder in that partnership, given that the vaccine candidate relies on technology developed by Hill and Gilbert and owned by Vaccitech. A deeper look into Vaccitech offers a clue as to why the company’s name has been absent from nearly all media reports on the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, as it demolishes the much-touted claim that the vaccine is “nonprofit” and offered at low cost for charitable reasons.

Vaccitech: Doing Well by Doing “Good”?

The official reason Sarah Gilbert and Adrian Hill created Vaccitech in 2016 perThe Times is because “Oxford’s researchers [are] encouraged to form companies to commercialize their work.” Vaccitech, like other “commercialized” Oxford research enterprises, was spun out of the Jenner Institute via the university’s commercialization arm, Oxford Science Innovations, which is currently Vaccitech’s largest stakeholder at 46 percent. Hill and Gilbert are reported to maintain a 10 percent stake in the company.

The largest investor in Oxford Science Innovations, and by extension one of the largest shareholders in Vaccitech, is Braavos Capital, the venture-capital firm started in 2019 by Andrew Crawford-Brunt, Deutsche Bank’s long-time global head of equity trading at its London branch. Through its stake in Oxford Science Innovations, Braavos owns about 9 percent of Vaccitech.

Prior to COVID-19, Vaccitech’s main focus, especially last year, was the development of a universal vaccine for the flu. Vaccitech’s efforts in this regard were praised by Google, which is also invested in Vaccitech. At the same time, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation was funding research to develop a universal flu vaccine, reportedly because the field of influenza vaccinology was not yet able “to design a flu vaccine that would protect broadly against the strains of flu that infect people every winter and those in nature that could emerge to trigger a disruptive and deadly pandemic,” according to a STAT News report from last year. The Gates Foundation effort originally partnered with Google’s cofounder Larry Page and his wife Lucy.

To fully finance Hill and Gilbert’s Vaccitech, and specifically its quest to develop a universal flu vaccine, Oxford Science Innovations sought £600 million from “outside investors,” chief among them the Wellcome Trust and the venture-capital arm of Google, Google Ventures. This means that Google is poised to make a profit from the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine at a time when its video platform YouTube has moved to ban COVID-19 vaccine–related content that shines a negative light on COVID-19 vaccines, including the Oxford-AstraZeneca candidate. Other investors in Vaccitech include Sequoia Capital’s Chinese branch and the Chinese pharmaceutical company Fosun Pharma. In addition, the UK government has put an estimated £5 million into the company and is also expected to make a return on the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine.

Information on the profit motive behind the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine has been muddied due to the extensive media promotion of the claim that Hill and Gilbert will not be collecting royalties on the vaccine and that AstraZeneca is not making a profit off the vaccine. However, this is only true until the pandemic is “officially” declared over, and the virus is labeled a persistent or seasonal condition that will require the mass administration of COVID-19 vaccines at regular intervals and possibly annually. Sky News reported that the determination of when the pandemic is over “will be based on the views of a range of [unspecified] independent bodies.” At that point, both Vaccitech and Oxford will obtain royalties from AstraZeneca’s sales of the vaccine.

Those tied to the vaccine have been at the center of promoting the idea that the COVID-19 vaccine will soon become an annual affair. For instance, in early May, John Bell—an Oxford medical professor and an “architect” of the Oxford-AstraZeneca partnership—told NBC News, “I suspect we may need to have relatively regular vaccinations against coronaviruses going into the future,” adding that the vaccine would likely be needed every year like the flu vaccine. NBC News failed to note that the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine in which Bell is involved stands to significantly benefit financially if that does come to pass.

More recently, Bell told The Week that, “should there prove to be a market for regular vaccinations against coronavirus in the future, ‘there is some money to be made.’” Such sentiments have been echoed by Pascal Soriot, the CEO of AstraZeneca, who told Bloomberg last month that the company stood to make a “reasonable profit” once the pandemic was declared over and COVID-19 deemed a seasonal illness requiring regular vaccinations. On this matter, Vaccitech’s CEO, Bill Enright, stated that Vaccitech investors would receive a “big chunk of the royalties from a successful vaccine as well as ‘milestone’ payments” if and when the pandemic is declared over and COVID-19 vaccines become a seasonal event.

Vaccitech, in particular, appears quite certain that this possibility is slated to become reality. For all subsequent iterations of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, Vaccitech will reacquire a much larger percentage of rights to the vaccine, rights it is currently splitting with Oxford for the first iteration. Sky News has noted that the technology that Vaccitech owns “could drive the second generation of COVID-19 vaccines” and that it “has [already] received £2.3 million of public funding to develop it.”

US government officials such as Anthony Fauci have also signaled that the COVID-19 vaccine will require annual shots. Notably, the government, through Health and Human Service’s BARDA, has poured over $1 billion into the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine development. In addition to government officials, several recently published mainstream media reports have claimed that the “expert” consensus “seem[s] to be leaning toward an annual shot like the flu vaccine” with regard to the COVID-19 vaccine. For instance, Charles Chiu, a professor of infectious diseases at the University of California–San Francisco, recently told Salon, “This may end up being a vaccine that’s not a one-time thing or even a two-time thing . . . it may end up being what we call either a seasonal vaccine, or vaccine that needs to be administered every couple of years.”

Such hints about an annual COVID-19 vaccine from 2021 onward have recently become commonplace from the leading COVID-19 vaccine manufacturers themselves. For instance, on December 13, Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla was quoted by the Telegraph as saying, “How long this [vaccine] protection lasts is something we don’t know . . . I think it is a likely scenario that you will need periodical vaccinations.” Pfizer also recently issued a statement that noted that “we don’t know how the virus will change, and we also don’t know how durable the protective effect of any vaccination will be,” adding that its vaccine would be suitable “for repeated administration as booster shots” in the event that the vaccine only induces an immune response for a few months.

Then, this past Tuesday, Moderna released information that suggested immunity from its COVID-19 vaccine would only last several months, with Forbes writing that “the duration of neutralizing antibodies from the Moderna vaccine will be relatively short, potentially less than a year,” an outcome that would favor the push for an annual COVID-19 shot. The developer of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine, Ugur Sahin of BioNTech, also stated on Tuesday that “the virus will stay with us for the next 10 years. . . . We need to get used to the fact there’ll be more outbreaks.” He later added that “if the virus becomes more efficient . . . we might need a higher uptake of the vaccine for life to return to normal,” implying that these regular outbreaks he foresees occurring over the next ten years would be correlated with increased vaccine administration.

Quotes from the developers of the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine themselves also point to a pandemic-dominated future and a desire for the crisis to be prolonged so that the vaccine can be widely distributed. Gilbert told the UK Independent in August that she believes COVID-19 is just the beginning and that COVID-like pandemics will become more frequent in the near future. The Jenner Institute vaccine team seems so determined to create the COVID vaccine that, in June, Hill was quoted by the Washington Postas stating that he wanted the pandemic to stick around, saying, “We’re in the bizarre position of wanting COVID to stay, at least for a little while. But cases are declining.” He also stated that his team was in “a race against the virus disappearing.”

With the vaccine developers, “medical experts,” government officials, and the CEOs of major vaccine manufacturers all agreeing that a seasonal COVID-19 vaccine is an increasingly likely outcome, it is worth considering a possible ulterior motive regarding the initial “nonprofit” model being used by the Jenner Institute/Vaccitech and AstraZeneca for their joint COVID-19 vaccine.

Given that vaccine guidance in several countries states that each dose of the multidose COVID-19 vaccine must be produced by the same manufacturer as previous doses, the implication is that in the event of a need for periodic COVID-19 vaccine variants, those who initially received the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine would likely be required to receive that same “brand” of vaccine seasonally. In other words, those who initially received the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine would likely be required, not just to receive a second dose of the same “brand,” but continue receiving that same “brand” of vaccine every year. Notably, no interaction studies have yet been conducted on the interactions between the COVID-19 vaccines and other medications as well as other vaccines.

If this turns out to be the case, it would certainly behoove the Oxford-Vaccitech-AstraZeneca team to want their vaccine to be the most widely used one in the first year in order to guarantee the largest market for subsequent annual COVID-19 vaccines. This could be a possible motive behind the efforts of the Oxford-AstraZeneca partnership “to supply the entire world with the Oxford jab” and to supply the vaccine “to the most vulnerable groups to COVID-19.” This vaccine has already been purchased, even before regulatory approval, by governments around the world, including in Europe, North America, Australia, and most Latin American countries.

The Wellcome Trust

Adrian Hill currently holds a senior position at the Wellcome Trust’s Centre for Human Genomics. The Wellcome Trust is a scientific charity based in London, established in 1936 with funds from pharmaceutical magnate Henry Wellcome. As previously mentioned, Wellcome founded the pharmaceutical company that eventually became the industry giant GlaxoSmithKline. Today, the Wellcome Trust has a $25.9 billion endowment and engages in philanthropic endeavors, including funding clinical trials and research.

Hill has been closely tied to Wellcome for decades. In 1994, he participated in the founding of the Wellcome Centre for Human Genetics and was awarded a Wellcome Trust Principal Research Fellowship the following year. He became a Wellcome professor of human genetics in 1996.

The Wellcome Centre for Human Genetics website boasts of the large-scale genetic mapping they’ve conducted in Africa. The center also publishes papers that explore genetic dispositions in relation to male fertility and “reproductive success.” The crossroads between race and genes is important in the center’s work, as an entire working group at the center, the Myers Group, is dedicated to mapping the “genetic impacts of migration events.” The center also funded a paper that argued that so long as eugenics is not coercive it’s an acceptable policy initiative. The paper asks, “Is the fact that an action or policy is a case of eugenics necessarily a reason not to do it?” According to Hill’s page on the Wellcome Trust site, race and genetics have long played a central role in his scientific approach, and his group currently focuses on the role genetics plays in African populations with regard to susceptibility to specific infectious diseases.

Of even greater concern, last year Science Mag reported that Wellcome was accused by both a whistleblower and the University of Cape Town South Africa of illegally exploiting hundreds of Africans by “commercializing a gene chip without proper legal agreements and without the consent of the hundreds of African people whose donated DNA was used to develop the chip.” Jantina de Vries, a bioethicist at the University of Cape Town South Africa, told the journal that it was “clearly unethical.” Since the controversy, other African institutions and peoples such as the indigenous Nama people of Namibia have demanded that Wellcome return the DNA it collected.

The Wellcome Centre regularly cofunds the research and development of vaccines and birth control methods with the Gates Foundation, a foundation that actively and admittedly engages in population and reproductive control in Africa and South Asia by, among other things, prioritizing the widespread distribution of injectable long-acting reversible contraceptives (LARCs). The Wellcome Trust has also directly funded studies that sought to develop methods to “improve uptake” of LARCs in places such as rural Rwanda.

As researcher Jacob Levich wrote in the Palgrave Encyclopedia of Imperialism and Anti-Imperialism, LARCs afford women in the Global South “the least choice possible short of actual sterilization.” Some LARCs can render women infertile for as long as five years, and, as Levich argues, they “leave far more control in the hands of providers, and less in the hands of women, than condoms, oral contraceptives, or traditional methods.”

One example is Norplant, a contraceptive implant manufactured by Schering (now Bayer) that can prevent pregnancy for up to five years. It was taken off the US market in 2002 after more than fifty thousand women filed lawsuits against the company and the doctors who prescribed it. Seventy of those class action suits were related to side effects such as depression, extreme nausea, scalp-hair loss, ovarian cysts, migraines, and excessive bleeding.

Slightly modified and rebranded as Jadelle, the dangerous drug was promoted in Africa by the Gates Foundation in conjunction with USAID and EngenderHealth. Formerly named the Sterilization League for Human Betterment, EngenderHealth’s original mission, inspired by racial eugenics, was to “improve the biological stock of the human race.” Jadelle is not approved by the FDA for use in the United States.

Another scandal-ridden LARC is Pfizer’s Depo-Provera, an injectable contraceptive used in several African and Asian countries. The Gates Foundation and USAID have collaborated to fund this drug’s distribution and introduce it into the health-care systems of countries including Uganda, Burkina Faso, Nigeria, Niger, Senegal, Bangladesh, and India.

Andrew Pollard, director of the Oxford Vaccine Group, where Hill’s Jenner Institute resides, is enmeshed with the Gates Foundation. His employer, the University of Oxford, has received $11 million for vaccine development research from the foundation over the past three years and $208 million in grants over the past decade. In 2016, the Gates Foundation gave $36 million to a team of researchers that was headed by Pollard for vaccine development. In addition, Pollard’s private laboratory is funded by the Gates Foundation. Given this, it should come as no surprise that the Global Alliance for Vaccine Initiative (GAVI), a public-private partnership founded and currently funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, plans to distribute the Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID-19 vaccine to low-income, predominantly African and Asian, countries once it’s approved.

The Galton Institute: Eugenics for the Twenty-First Century

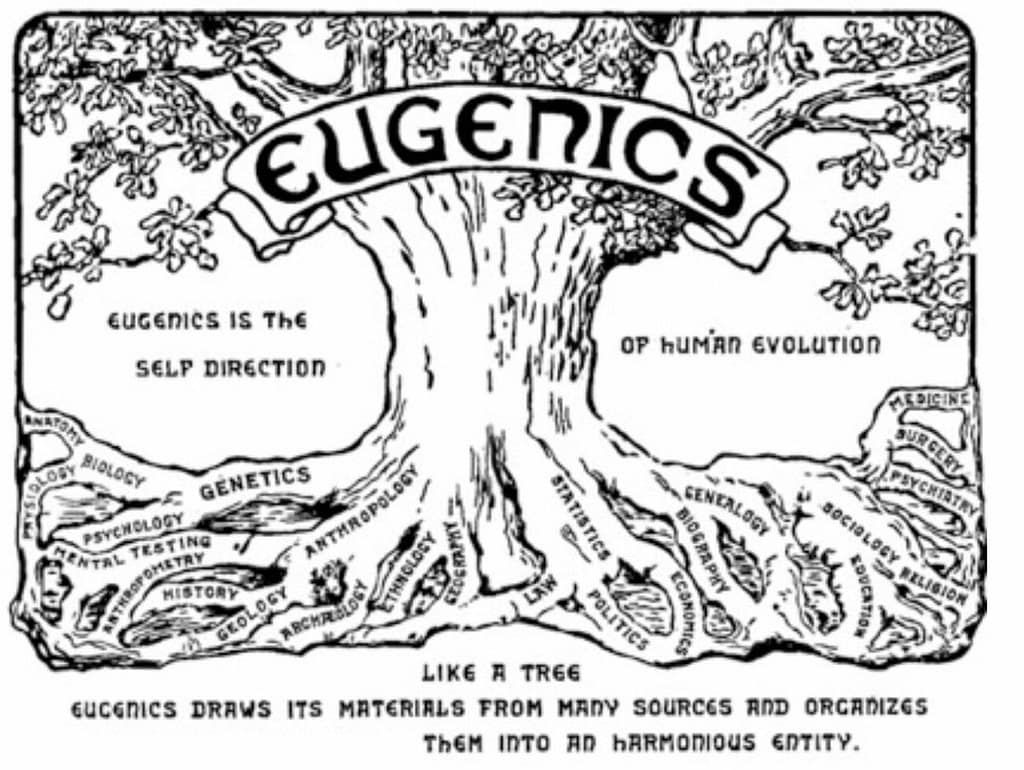

Both the Wellcome Trust and Adrian Hill share a close relationship with the most infamous eugenics society in Europe, the British Eugenics Society. The Eugenics Society was renamed the Galton Institute in 1989, a name that pays homage to Sir Francis Galton, the so-called father of eugenics, a field that he often described as the “science of improving racial stock.”

In the case of the Wellcome Trust, the Trust’s library is the guardian of the Eugenics Society historical archives. When the Wellcome Trust first set up its Contemporary Medical Archive Center, the first organizational archive it sought to acquire was tellingly that of the Eugenics Society–Galton Institute. Wellcome’s website describes the Eugenics Society’s original purpose as “to increase public understanding of heredity and to influence parenthood in Britain, with the aim of biological improvement of the nation and mitigation of the burdens deemed to be imposed on society by the genetically ‘unfit’.” It also states the interests of the society’s members “ranged from the biology of heredity, a subject that developed rapidly during the first half of the 20th century, to the provision of birth control methods, artificial insemination, statistics, sex education and family allowances.” Lesley Hall, Wellcome’s senior archivist, has referred to Francis Galton, a racist eugenicist, as an “eminent late nineteenth century polymath” in her discussion of the Eugenics Society archive held at Wellcome.

Several top governance positions at the former British Eugenics Society, now the Galton Institute, include individuals who originally worked at the Wellcome Trust, including the Galton Institute’s president Turi King. Elena Bochukova, a current Galton Council Member and Galton lecturer, previously worked under the direction of Adrian Hill at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics. The Galton Institute’s senior genetics researcher, Jess Buxton, was previously a “genetics researcher” at the Wellcome Trust and then went on to carry out independent research financed by Wellcome. Her research, which is particularly race oriented, includes creating the first genetic sequence map of a native Nigerian. Moreover, Adrian Hill himself spoke at the Eugenics Society–Galton Institute at the celebration of their 100th anniversary in 2008.

The Galton Institute publishes what they now call the Galton Review, previously titled the Eugenics Review, where various members of the self-proclaimed “learned society” publish papers focused on population issues, genetics, evolutionary biology, and fertility.

A look at early issues of the Eugenics Review shines a light on Galton’s original ambitions. In the 1955 issue titled “The Immigration of Colored People,” an author asks, “What will become of our national character, good workmanship etc. in the course of a few decades if this immigration of negroes and negroids continues unchecked?” The article ends with an appeal to readers to write their parliamentary representatives and urge them that in view of “racial betterment or deterioration” something must be done urgently to “check the present influx of africans and other negroids.”

Today, it appears that the Galton Institute continues to see the immigration of racial minorities into European cities as an unchecked threat. David Coleman, an Oxford professor of demographics and a fellow at the institute runs an anti-immigration organization and advocacy group called MigrationWatch, whose mission is to preserve the European culture of the UK by lobbying the government to stem legal immigration and publishing data that supposedly demonstrates the biological and cultural threat of increasing immigration.

A 1961 issue of the Eugenics Review titled “The Impending Crisis” claims the function of the institute’s upcoming conference is “to honor Margaret Sanger” and describes the population crisis as “quantity threatening quality.”

Sanger, known as the “pioneer of the American birth control movement,” was a staunch advocate for promoting “racial betterment” and the key architect of the Negro Project, which she claimed “was established for the benefit of the colored people.” But as medical ethics fellow at Harvard Medical School, Harriet Washington, argues in her book Medical Apartheid, “The Negro Project sought to find the best way to reduce the black population by promoting eugenic principals.” Sanger was an American member of the British Eugenics Society.

Another early member of the Galton Institute was John Harvey Kellogg, prominent business man and eugenicist. Kellogg founded the Race Betterment Foundation and argued that immigrants and nonwhites would damage the American gene pool. Yet another example is Charles Davenport, a scientist known for his collaborative research efforts with eugenicists in Nazi Germany and his contributions to Nazi Germany’s brutal racial policies, who was vice president of the Galton Institute in 1931.

Another more recent member of the Galton Institute was David Weatherall, for whom the Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine at Oxford is named. Weatherall was a member of the Galton Institute when it was still named the Eugenics Society, and he remained a member until his death in 2018. Weatherall, who was knighted by the British monarch in 1987 for his contributions to science, addressed the Galton Institute on numerous occasions and gave a senior lecture on genetics at the institute in 2014, of which no transcript or video is available. As an Oxford professor, Weatherall was Adrian Hill’s doctoral adviser and eventually his boss when Hill began working at the Weatherall Institute conducting immunogenic research in Africa. A key fixture of the Weatherall Institute of Molecular Medicine since its founding is Walter Bodmer, a former president of the Galton Institute.

While the Galton Institute has attempted to distance itself from its past of promoting racial eugenics with surface-level public relations efforts, it has not stopped family members of the infamous racist from achieving leadership positions at the institute. Emeritus professor of molecular genetics at the Galton Institute and one of its officers is none other than David J. Galton, whose work includes Eugenics: The Future of Human Life in the 21st Century. David Galton has written that the Human Genome Mapping Project, originally dreamt up by Galton’s former president Walter Bodmer, had “enormously increased . . . the scope for eugenics . . . because of the development of a very powerful technology for the manipulation of DNA.”

This new “wider definition of eugenics,” Galton has said, “would cover methods of regulating population numbers as well as improving genome quality by selective artificial insemination by donor, gene therapy or gene manipulation of germ-line cells.” In expanding on this new definition, Galton is neutral as to “whether some methods should be made compulsory by the state, or left entirely to the personal choice of the individual.”

Who Gets the Safest Vaccines?

Considering the degree to which the players and institutions behind the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine (including the lead developer) are tied and connected to institutions that have been instrumental in the rise and perpetuation of racial eugenics, it’s concerning that this particular vaccine is being portrayed by scientists and media alike as the COVID-19 vaccine for the poor and the Global South.

The Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine sells at a fraction of the cost of its COVID-19 vaccine competitors—running between 3 and 5 dollars per dose. Moderna and Pfizer cost 25 to 37 dollars and 20 dollars per dose, respectively. As CNN recently reported, the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine will “be far easier to transport and distribute in developing countries than its rivals,” several of which require complicated and costly cold supply chains. When the Thomson Reuters Foundation asked several experts which COVID-19 vaccine could “reach the poorest soonest,” all declared a preference for the Oxford-AstraZeneca candidate.

There is also the added fact that a host of safety issues have come to surround the vaccine. Recently, on November 21, a forty-year-old participant in AstraZeneca’s clinical trial who lives in India sent a legal notice to the Serum Institute of India alleging that the vaccine caused him to develop acute neuroencephalopathy, or brain damage. In the notice, the participant said he “must be compensated, in the least, for all the sufferings that he and his family have undergone and are likely to undergo in the future.”

In response, the Serum Institute claimed the participant’s medical complications are unrelated to the vaccine trial and said it would take “legal action” against the brain-damaged participant for maligning the company’s reputation, seeking damages in excess of $13 million. “This is the first time I have ever heard of a sponsor threatening a trial participant,” Amar Jesani, editor of the Indian Journal of Medical Ethics, said of the incident. The Serum Institute has received at least $18.6 million from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and has a deal with AstraZeneca to manufacture a billion doses of the vaccine.

Other manufacturers chosen by Oxford-AstraZeneca to produce their vaccine are also no strangers to controversy. For instance, their manufacturing partner in China, Shenzhen Kangtai Biological Products, has been at the center of controversy for years, especially after seventeen infants died from its hepatitis B vaccine in 2013. The New York Times citedYanzhong Huang, a senior fellow for global health at the Council on Foreign Relations, as saying, “Imagine if a similar scandal is reported again in China. . . . It’s not just going to undermine the confidence of the company manufacturing the vaccine, it’s also going to hurt the reputation of AstraZeneca itself and their vaccine, too.”

In another example, the manufacturing partner chosen to produce the vaccine in the US is the scandal-ridden company with ties to the 2001 anthrax attacks, Emergent Biosolutions. Emergent Biosolutions, previously known as BioPort, has a long track record of knowingly selling and marketing products that were never tested for safety and efficacy, including its anthrax vaccine BioThrax and its biodefense product Trobigard. The current head of quality control for Emergent Biosolutions’ lead manufacturing facility in the US has no expertise in pharmaceutical manufacturing and is instead a former high-ranking military intelligence official who operated in Iraq, Afghanistan, and beyond.

The issues raised by their decision to partner with manufacturers with dark histories of product safety issues are compounded by the adverse reactions reported in the Oxford-AstraZeneca trials as well as the ways in which those trials have been conducted. In September, AstraZeneca was forced to pause its experimental COVID-19 vaccine trial after a woman in the UK developed a “suspected serious reaction” that the New York Times reported was consistent with transverse myelitis. TM is a neurological disorder characterized by inflammation of the spinal cord, a major element of the central nervous system. It often results in weakness of the limbs, problems emptying the bladder, and paralysis. Patients can become severely disabled, and there is currently no effective cure.

Concern over an association between TM and vaccines is well established. A review of published case studies in 2009 documented thirty-seven cases of TM associated with various vaccines, including hepatitis B, measles-mumps-rubella, diphtheria, pertussis, tetanus, among others in infants, children, and adults. The researchers in Israel noted, “The associations of different vaccines with a single autoimmune phenomenon allude to the idea that a common denominator of these vaccines, such as an adjuvant, might trigger this syndrome.” Even the New York Times article on the AstraZeneca trial pause notes past “speculation” that vaccines might be able to trigger TM.

In July, an Oxford-AstraZeneca trial participant developed symptoms of TM, and the vaccine trial was paused at that time. An “independent panel” ultimately concluded the illness was unrelated to the vaccine, and the trial continued. Yet, as Nikolai Petrovsky from Flinders University told the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, these panels are typically made up of “biostatisticians and also medical representatives from the sponsor drug company running the trial.” Then, in October, a trial participant in Brazil died, though in that case, AstraZeneca suggested that the person was part of the control group and thus hadn’t received the COVID-19 vaccine.

According to Forbes, the AstraZeneca vaccine was ineffective at stopping the spread of coronavirus in their animal trials. All six monkeys injected with AstraZeneca’s COVID-19 vaccine became infected with the disease after being inoculated. All the monkeys were put to death, which means that it will remain unknown whether those monkeys would have suffered other adverse effects.

Another concern is that trial administrators gave the trial control group (for both human and animal trials) Pfizer’s Nimenrix, a meningitis vaccine, as opposed to a saline solution, which is regarded as the gold standard for controls because researchers can be sure the saline solution won’t cause any adverse reactions. Using Pfizer’s meningitis vaccine as the control placebo allows AstraZeneca to downplay any adverse reactions in its COVID-19 vaccine group by showing that the control group suffered adverse reactions as well. “The meningitis vaccine in the AstraZeneca trial is what I would call a ‘fauxcebo,’ a fake control whose real purpose is to disguise or hide injury in the vaccine group,” said Mary Holland, general counsel at Children’s Health Defense.

Eugenics under Another Name

Despite these safety concerns and clinical trial scandals, close to 160 countries have purchased the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine, and now reports are suggesting that India, the country with the second largest population on earth, is likely to approve this vaccine by next week.

As documented here, while the vaccine may be heralded as “vital for lower-income countries,” the Oxford-AstraZeneca project is no mere philanthropic pursuit. Not only is there a significant profit motive behind the vaccine, but its lead researcher’s connection to the British Eugenics Society adds another level of warranted scrutiny.

For those encountering stories of eugenicists, it’s common to dismiss such activity as that of “conspiracy theories.” However, it’s undeniable that several prominent individuals and institutions that remain active today have clear ties to eugenicist thinking, which was not so taboo just a few decades ago. Unfortunately, this holds true for the individuals and institutions associated with the Oxford-AstraZeneca COVID vaccine, who, as demonstrated in this article, immerse themselves in studies of race science and population control—primarily in Africa—while working closely with institutions that have direct and longstanding links to the worst of the eugenics movement.

As this series has shown, there are many concerns regarding the points where race and the COVID-19 vaccination campaign in the US and abroad intersect, both publicly and privately. Part 1 of this series raised questions about the policy-shaping role of the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security, which suggested that the US government make COVID-19 vaccines available to ethnic minorities and the mentally challenged first. Part 2 explained how in order to allocate COVID-19 vaccines in the US, health agencies are using a program created by Palantir, a company with a record of helping the US agencies target ethnic minorities through immigration policy and racist policing.

Furthermore, there are plans in place to exercise what could reasonably be described as economic coercion to pressure people to “voluntarily” get vaccinated. Such coercion will be obviously be more effective on poor and working communities, meaning communities of color will be disproportionately affected as well.

Considering these facts, and the case for scrutinizing the safety of Oxford-AstraZeneca’s “affordable” vaccine option made above, any harm caused by vaccine allocation policy in the US and beyond is likely to disproportionately affect poor communities, especially communities of color.

As such, the public should take all vaccine rollout policy assertions with a grain of salt, even when they come cloaked in language of inclusion, racial justice, and public health preservation. As the cofounder of the American Eugenics Society (later renamed Society for the Study of Social Biology) Frederick Osborn put it in 1968, “Eugenic goals are most likely to be attained under a name other than eugenics.”